Good scientific practice: Design of High Throughput Experiments and their Analysis

2023-01-17

Why are we here?

To consult the statistician after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination. He can perhaps say what the experiment died of.

Presidential Address to the First Indian Statistical Congress, 1938. Sankhya 4, 14-17.

R.A. Fisher, Pioneer of Statistics and Experimental Design

Design of High Throughput Experiments

This lecture is based on Chapter 13 of the book

Modern Statistics for Modern Biology

by Susan Holmes, Wolfgang Huber

https://www.huber.embl.de/msmb/

Topics

- Resource allocation & experimental design: a matter of trade-offs & good judgement

- Dealing with the different types of variability; partitioning variability

- Experiments, studies, …

- Power, sample size and efficiency.

- Transformations

- Things to worry about: dependencies, batch effects, unwanted variation.

- Compression, redundancy and sufficiency

- Computational best practices

The Art of “Good Enough”

- Experimental design rationalizes the tradeoffs imposed by having finite resources.

- Our measurement instruments have limited resolution and precision; often we don’t know these at the outset and have to collect preliminary data providing estimates.

- Sample sizes are limited for practical, economic, and sometimes ethical reasons.

- We may only be able to observe the phenomenon of interest indirectly rather than directly.

- Our measurements may be overlaid with nuisance factors over which we have limited control.

- There is little point in prescribing unrealistic ideals: we need to make pragmatic choices that are feasible.

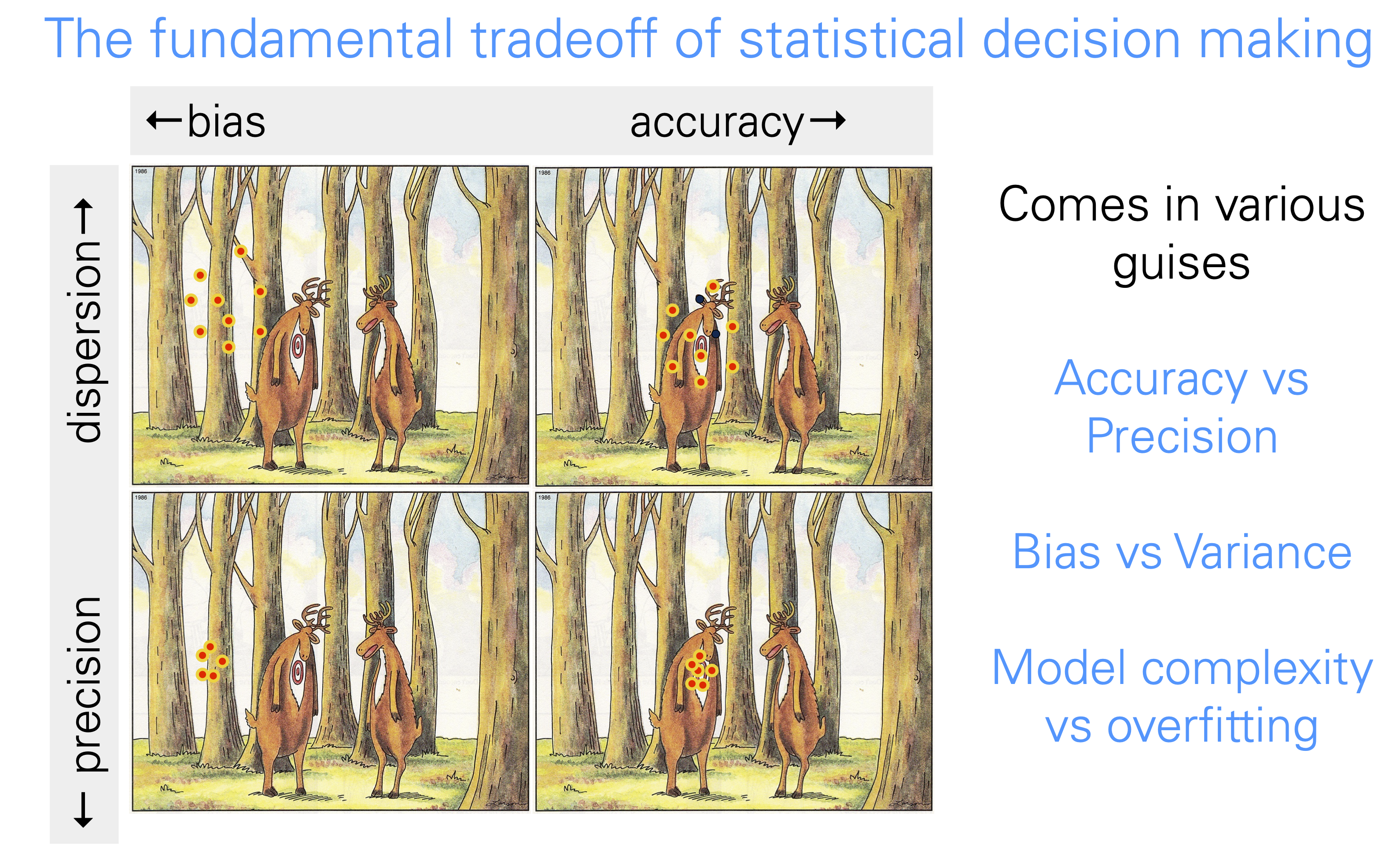

Accuracy vs precision

Types of studies / experiments

Experiment

- everything is exquisitely controlled

Retrospective observational studies

- we take what we get, opportunistic; no control over study participants, assignment of important factors, confounding

Prospective, controlled studies

- e.g., clinical trials

- randomization, blinding

- ethical constraints (incl. money and time).

Meta-analysis

- We did not design the experiments or studies ourselves, nor collect the data.

- Retrospective analysis of data that already happen to exist.

Illustration: experiment

Well-characterized cell line growing in laboratory conditions on defined media, temperature and atmosphere.

We administer a precise amount of a drug, and after 72h we measure the activity of a specific pathway reporter.

Illustration: challenges with studies

We recruit patients with a chronic disease and who fulfill inclusion criteria, and we ask them to take a drug each day exactly at 6 am. Before, and after 3 months, we perform a diagnostic test.

- People may forget to take the pill or take it at the wrong time.

- Some may feel that the disease got worse and stop taking the drug.

- Some may feel that the disease got better and stop taking the drug.

- Some may lead a healthy life-style, others drink, smoke and eat junk food.

- Maybe it’s not one disease but several

- And all of these factors may be correlated with each other in complex ways.

What to do about this?

- need much larger sample sizes than with an experiment

- randomization, blinding, documentation

Biological versus technical replicates

Imagine we want to test whether a weight loss drug works. Which of the following designs is better?

A person is weighed on milligram precision scales, with 20 replicates. He/she follows the diet, and four weeks later, (s)he is weighed again, with 20 replicates. The data are recorded by a specially trained technician.

20 people weigh themselves on their bathroom scales and self-report the number. Four weeks later, they weigh themselves and report again.

Some design decisions in HT biology are similar, if more subtle:

- sequencing libraries

- cell lines

- CRISPR guides

- drugs

Quiz

For reliable variant calling with current sequencing technology, you need ca. \(30\times\) coverage for a human genome.

In the 1000 Genomes Project, the average depth of the data produced was 5.1 for 1092 individuals. Why was that study design chosen?

\(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

What exactly is a technical versus biological replicate?

In fact, the terminology is too simplistic. Variation can occur at many different levels:

- different CRISPR guide RNAs for the same target gene

- different drugs for the same target protein

- different cell line (organoid, animal) models for the same biological system

- different measurement technologies (e.g., multiplexed immunohistochemistry vs imaging mass cytometry)

- different machines for the same technology

- different variants of the protocol

- different technician, lab

We use blocking and can use the tools of design matrices in linear models to record and account for it.

To the extent that we know about such nuisance factors and have kept track of them, we can (should) include them explicitly as bias terms in our analysis models.

If we did not keep track, we can try to use latent factor models (SVA, PEER, RUV) to identify them from the data.

Error models: Noise is in the eye of the beholder

The efficiency of most biochemical or physical processes involving nucleic acid polymers depends on their sequence content, for instance, occurrences of long homopolymer stretches, palindromes, GC content.

These effects are not universal, but can also depend on factors like concentration, temperature, which enzyme is used, etc.

When looking at RNA-Seq data, should we treat GC content as noise or as bias?

One person’s noise can be another’s bias

We may think that the outcome of tossing a coin is completely random.

If we meticulously registered the initial conditions of the coin flip and solved the mechanical equations, we could predict which side has a higher probability of coming up: noise becomes bias.

We use mathematical and probabilistic modelling as a method to bring some order into our ignorance—but keep in mind that such models are an expression of our subjective ignorance, not an objective property of the world.

A lack of units

Pre-modern measurement systems measured lengths in feet, ells, inches (first joint of an index finger), weights in stones, volumes in multiples of the size of a wine jar, etc.

In the International System of Units, meters, seconds, kilograms, amperes, … are defined based on universal physical constants.

There is no reliance on artefacts, and a meter measured by a lab in Canada using one instrument has the same meaning as a meter measured a year later by a lab in Heidelberg using a different instrument, by a space probe in the Kuiper belt, or by an extraterrestrial intelligence on Proxima Cen b.

Measurements in biology are, unfortunately, rarely that comparable.

Often, absolute values are not reported (these would require units), but only fold changes with regard to some local reference.

Even when absolute values exist (e.g., read counts in an RNA-Seq experiment) they usually do not translate into universal units such as molecules per cell or mole per milliliter.

Normalization

Dealing with the lack of units in many biological assays

- try to make measurements comparable to each other using some ‘arbitrary’ but at least consistent units

- only consider endpoints where the units cancel out (e.g., fold change)

Examples

- Sequence counts

- Mass spec intensities

- Fluorescence intensities (e.g. CODEX)

Btw, terrible name. It has nothing to do with normal distribution, vector norm, or right angles. Perhaps better would be “calibration”.

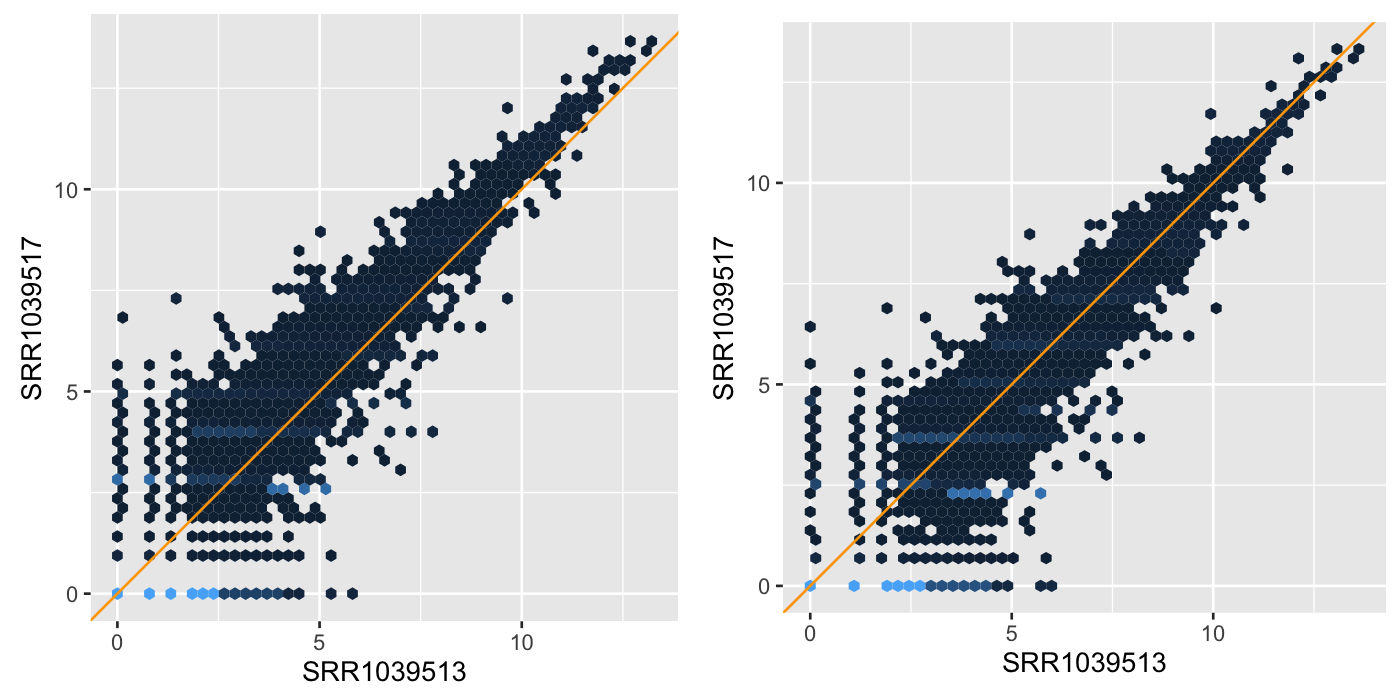

What is a good normalization method?

- If the normalization is ‘off’, we can have increased variability between replicates

- … and/or apparent systematic differences between different conditions that are not real

- \(\to\) false positives, false negatives

What do we want from a good normalization method:

- remove technical variation

- but keep biological variation

Possible figure of merit?

- signal-to-noise ratio, computed from pos. and neg. controls, replicates

Occam’s razor

If one can explain a phenomenon without assuming this or that hypothetical entity, there is no ground for assuming it.

One should always opt for an explanation in terms of the fewest possible causes, factors, or variables.

Regular and catastrophic noise

Regular noise: can be modeled by simple probability models (independent normal, Poisson distributions; or mixtures such as Gamma-Poisson or Laplace)

Can use relatively straightforward methods to take regular noise into account

Real world is more complicated: measurements can be completely off the scale (sample swap, contamination, software bug, …)

Multiple errors often come together: e.g., a whole microtiter plate went bad, affecting all data measured from it.

Such events are hard to model or even correct for—our best chance is data quality assessment, outlier detection and documented removal.

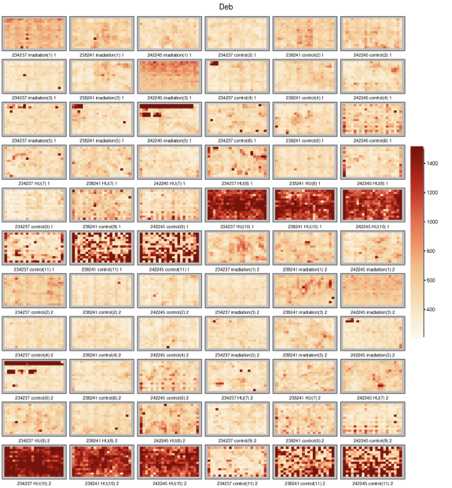

RNAi screen example

Keeping track: Dailies

A film director will view daily takes, to correct potential lighting, shooting issues before they affect too much footage. It is a good idea not to wait until all the runs of an experiment have been finished before looking at the data.

Intermediate data analyses and visualizations will track eventual unexpected sources of variation in the data and enable you to adjust the protocol.

It is important to be aware of sources of variation as they occur and adjust for them.

Vary one factor at a time

Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine (1020) lists seven rules of experimental design, including the need for controls and replication, the danger of confounding and the necessity of changing only one factor at a time.

This dogma was overthrown in the 20th century by RA Fisher.

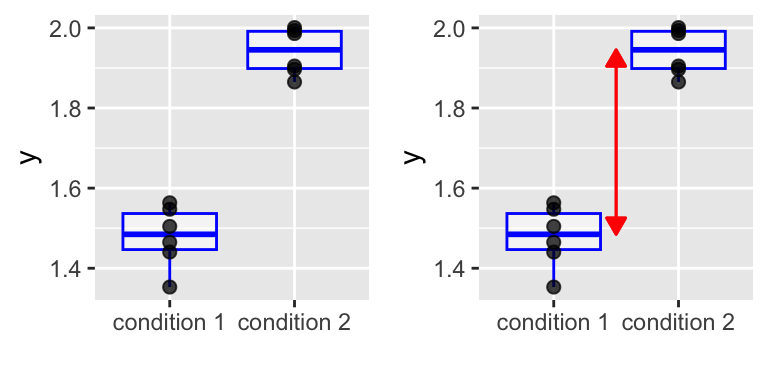

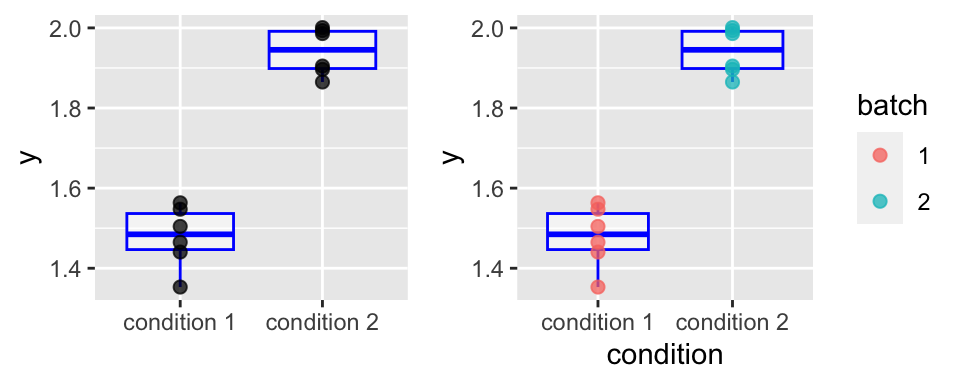

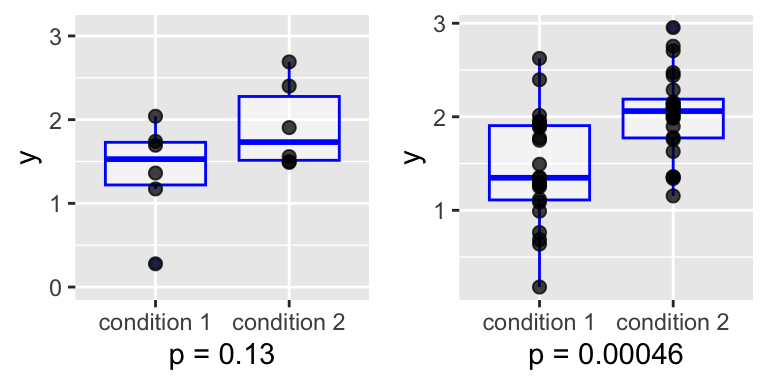

A toy example: two-group comparison

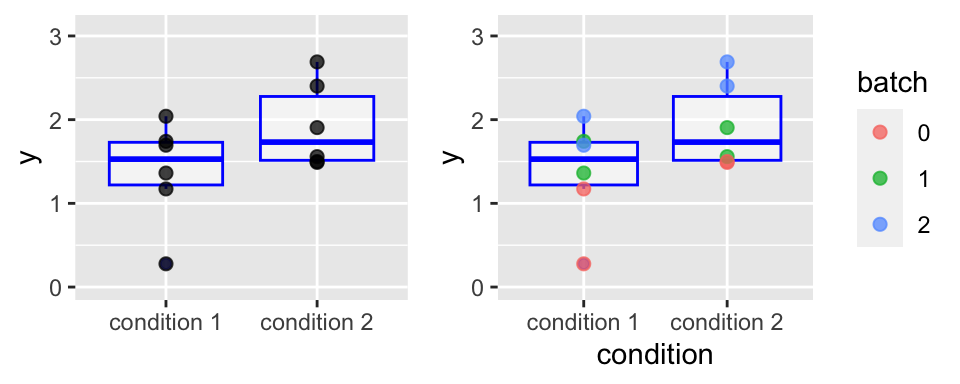

However, suppose the experiment was done in two “batches”, and we color the data according that:

We cannot conclude because of confounding.

Now suppose there is no such fatal confounding, but an unknown batch effect that is balanced between the conditions, and effectively causes higher noise levels. Then, the previous sample size (2 x 6) is not enough. With 2 x 24, it looks better:

Lessons from the toy example

- Success of an experiment: detect a difference iff it is truly there, and for the right reasons

- Spread (sd, var) matters as much as the effect size

Depends on:

- Effect size (unchangeable)

- Control and documentation of all factors (block effects, date / time / operator etc.).

- Noise (irreducible variability in measurements): \(\sigma\)

- Sample sizes: remember standard error of mean is \(\sim\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)

Decomposition of variability: analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Analysis of Variance Table

Response: y

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

condition 1 0.8828 0.8828 2.723 0.1299

Residuals 10 3.2420 0.3242 \(\quad\)

Analysis of Variance Table

Response: y

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

condition 1 0.88280 0.88280 8.4591 0.019635 *

batch 2 2.40714 1.20357 11.5328 0.004398 **

Residuals 8 0.83489 0.10436

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Blocking: the case of paired experiments.

Darwin’s Zea Mays experiment:

pot pair type height

1 I a cross 23.500

2 I a self 17.375

3 I b cross 12.000

4 I b self 20.375

5 I c cross 21.000

6 I c self 20.000 pair

type a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o

cross 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

self 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1- 15 pairs of plants, each with two different pollination methods, across 4 pots.

- a balanced design: all the different factor combinations have the same number of observation replicates.

- particularly easy to analyse

Paired t-test is equivalent to a 2-way ANOVA

Paired t-test

data: height[type == "self"] and height[type == "cross"]

t = -2.148, df = 14, p-value = 0.0497

alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-5.229434169 -0.003899165

sample estimates:

mean difference

-2.616667 Analysis of Variance Table

Response: height

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

type 1 51.352 51.352 4.6139 0.0497 *

pair 14 86.264 6.162 0.5536 0.8597

Residuals 14 155.820 11.130

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 typeself

-2.616667 t-test comments

The proof that the \(t\)-statistic follows a certain \(t\)-distribution assumes that observations are independent and follow a normal distribution: this is a sufficient, but not necessary, condition.

Deviation from normality (heavier tails): test typically maintains type-I error control (it may loose some power).

Options: use simulations or permutations; use a different test (e.g., Wilcoxon)

Deviation from independence: type-I error control is lost, p-values will likely be totally wrong (e.g., for positive correlation, too optimistic).

No easy options:

- try to model the dependence (multivariate analysis)

- remove it

- empirical null (Efron et al.)

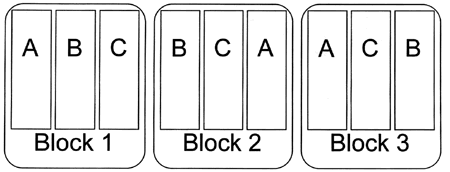

“Block what you can, randomize what you cannot”

(George Box, 1978)

Often we don’t know which nuisance factors will be important, or we cannot plan for them ahead of time.

In such cases, randomization is a practical strategy: at least in the limit of large enough sample size, the effect of any nuisance factor should average out.

Randomized Complete Block Design

“The design space is divided into uniform units to account for any variation so that observed differences within units are largely due to true differences between treatments. Treatments are then assigned at random to the subjects in the blocks - once in each block. The defining feature of the Randomized Complete Block Design is that each block sees each treatment exactly once.” (Trudi Grant)

Randomization decreases bias

- Humans are bad at assigning treatments truly at random

- Random assignment reduces unconscious bias (special samples treated differently, “balancing things out”, …)

- Randomization also helps with unknown nuisance factors.

Randomization helps inference

- if the sample is randomly generated from a population, we can infer something about the population we drew from

Random does not mean haphazardly

- Need to use a random number generator and a seed.

There is also rich literature on deterministic, balanced block designs.

Thinking of computational methods like we do of biological assays

Many biological assays are so fiddly and fickle that we always use them together with positive and negative controls (Western blots, CRISPR, PCR…)

With sufficiently complicated computational analyses, it can be worthwhile to think of them in the same way.

How many replicates do I need?

In well-controlled experiment: rule of thumb, \(n\le 3\).

In a study: dozens, hundreds.

If a factor of interest is continuous (e.g. time, temperature, concentration) and sampled at many points, there usually no need for replication within its levels.

Effective sample size for dependent data.

A sample of independent observations is more informative than the same number of dependent observations. \(\Rightarrow\) Dependent data require larger samples. Intuition: each sample contains less information.

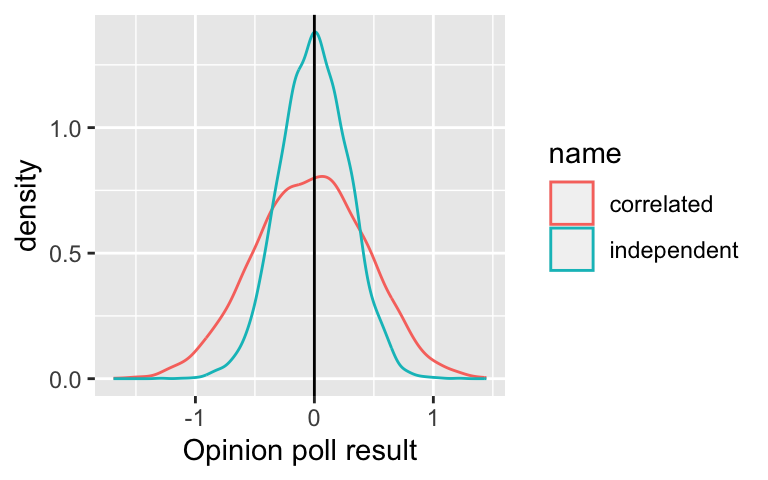

Consider an opinion poll. We knock at people’s doors and ask them a question.

- Scenario 1: pick \(n\) people at \(n\) random places throughout the country.

- Scenario 2: to save travel time, you pick \(n/3\) random places and then at each of these interview three people who live next door to each other.

In both cases, \(n\) people are polled is \(n\). But if we assume that people living in the same neighborhood are more likely to have similar opinions, the data from Scenario 2 are (positively) correlated.

Simulation: “opinions” in a population of 100 people are \(N(0,1)\). We want to estimate the mean by sampling. In scenario 1, we ask 12 randomly selected people. In scenario, we ask 4 randomly selected people as well as two of their direct neighbours.

Time course: equalize the dependence structure by taking more frequent samples when there is more “going on”.

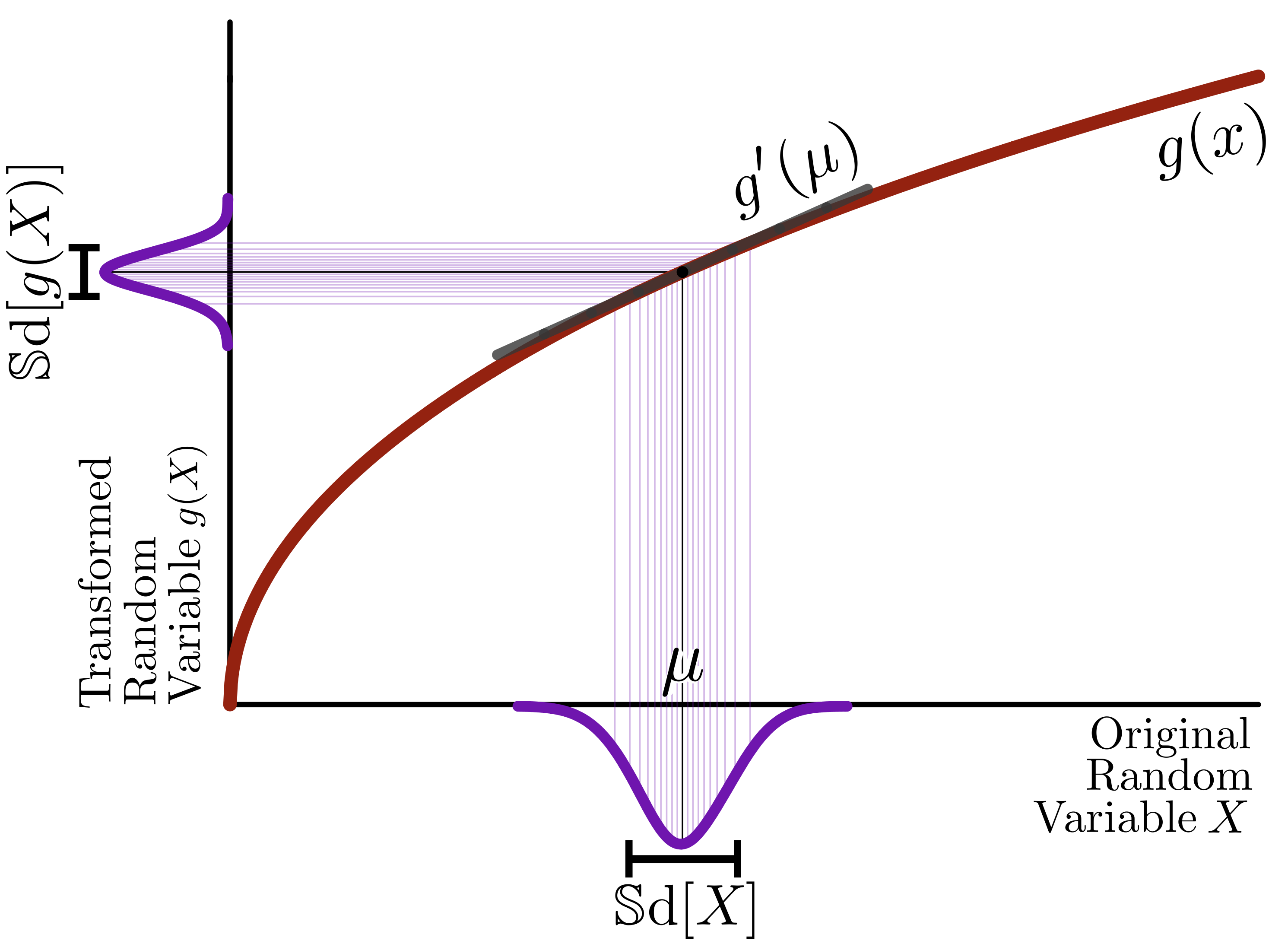

Data transformations

\[\begin{equation} X_{\text{obs}} = f(\theta) + \varepsilon \end{equation}\]

Homoskedastic: \(\quad\text{sd}(\varepsilon)=\text{const.}\)

Heteroskedastic: e.g.,

- multiplicative error: \(\quad\text{sd}(\varepsilon)\sim f(\theta)\)

- Poisson noise: \(\quad\text{var}(\varepsilon)\sim f(\theta)\)

- multiplicative error: \(\log(X)\)

- Poisson noise: \(\sqrt X\)

Examples:

- Fluorescence based assays: additive + multiplicative (Rocke and Durbin 2001)

- RNA-Seq: Poisson + multiplicative.

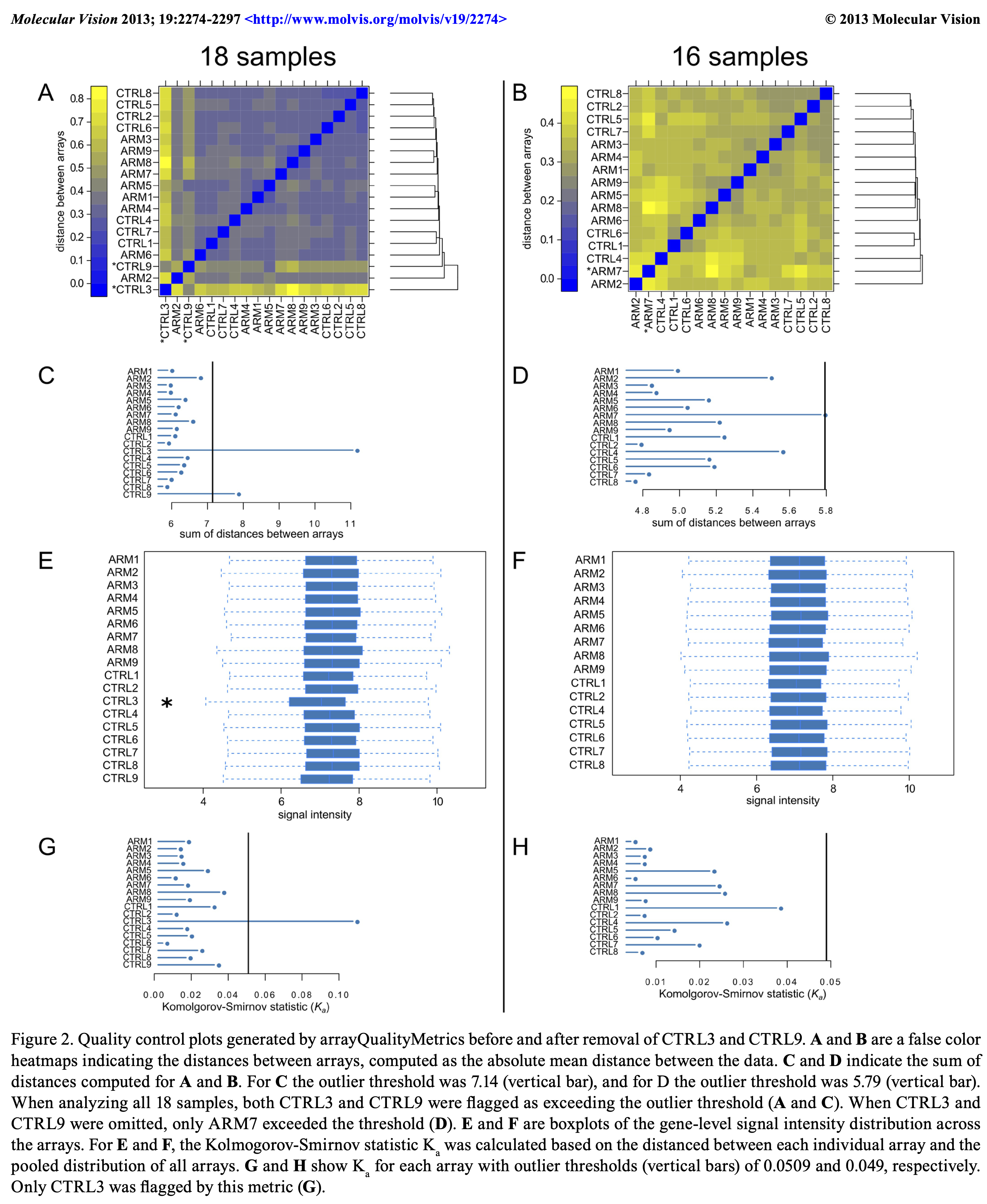

Data quality assessment and quality control

- QA: measure and monitor data quality

- QC: remove bad data

Pervade all phases of analysis: raw data, transformation, summarization, model fitting, hypothesis testing, screening for ‘’hits’’. Diagnostics and metrics:

- Feature value range (Boxplot, ECDF) across samples

- Joint distributions (scatter plots, heatmaps, sample-sample or feature-feature correlation matrices)?

- Correlation of replicates vs between biological conditions

- Evidence of batch effects (categorical, continuous)—–explicitly known or latent.

iSEE package: PBMC4k example, CYTOF example

MatrixQCVis package:

Henry Ford (possibly apocryphal): ‘’If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.’’: quality as fitness for purpose, versus adherence to specifications.

Not easy to nail down (or mathematically define) quality, the word is used with many meanings. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quality_(business)

Longitudinal Data

Longitudinal data have time as a covariate.

handful of time points (e.g. response of a cell line measured 48h, 72h and 84h after exposure to a drug) vs a long and densely sampled time series (e.g. patch clamp data in electrophysiology or movie from life cell microscopy).

in 1st case, think of time as just another experimental factor, like concentration or choice of drug. One analysis strategy could be to first identify the “best”, or biologically most indicative, time point, and then focus on that. Or whether there is any effect at all, regardless of the time.

in 2nd case, time series, we’ll often want to fit dynamical models to the data. We have many choices:

- (Hidden) Markov models

- Change point detection

- Ordinary differential equations or reaction-diffusion models

- Piece-wise deterministic stochastic processes

- Autoregressive models

- Non-parametric smoothing followed by clustering or classification into prototypic shapes

Don’t Pretend You Are Dumb

- Pros and cons of “unbiased” approaches

Examples include:

Clustering vs (semi-)supervised classification

Multiple testing / hypothesis weighting (\(\to\) independent hypothesis weighting, et al.)

Feature scaling

Dichotomization is bad

Grouping / discretization of continuous variables

Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: a bad idea

Royston, Altman, Sauerbrei

Statistics in Medicine 2006

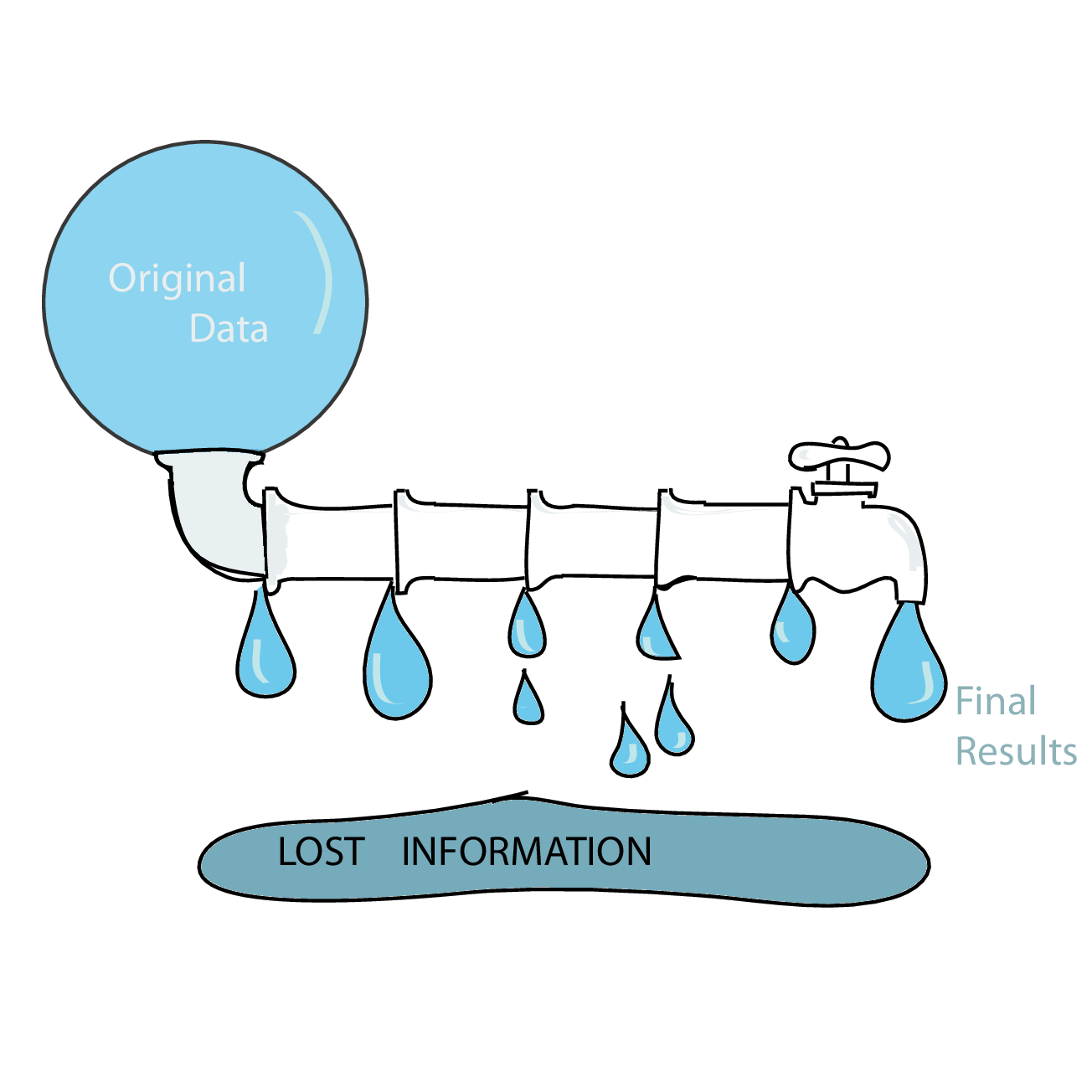

Leaky pipelines and statistical sufficiency

Data analysis pipelines in high-throughput biology often work as funnels that successively summarise and compress the data. In high-throughput sequencing, we may start with individual sequencing reads, then align them to a reference, then only count the aligned reads for each position, summarise positions to genes (or other kinds of regions), then “normalize” these numbers by library size, etc.

At each step, we loose some information, and it is important to make sure we still have enough information for the task at hand. The problem is particularly burning if we use a data pipeline built from a series of separate components without enough care being taken ensuring that all the information necessary for ulterior steps is conserved.

Statisticians have a concept for whether certain summaries enable the reconstruction of all the relevant information in the data: sufficiency. E.g., in a Bernoulli random experiment with a known number of trials, \(n\), the number of successes is a sufficient statistic for estimating the probability of success \(p\).

In a 4-state Markov chain (A,C,G,T) such as the one we saw in Lecture 2, what are the sufficient statistics for the estimation of the transition probabilities?

Iterative approaches akin to what we saw when we used the EM algorithm can sometimes help avoid information loss. For instance, when analyzing mass spectroscopy data, a first run guesses at peaks individually for every sample. After this preliminary spectra-spotting, another iteration allows us to borrow strength from the other samples to spot spectra that may have been labeled as noise.

Sharpen Your Tools: Reproducible Research

Analysis projects often begin with a simple script, exploration, prototyping.

- Many ideas are tried, dissmissed, adapted.

- More data come in, external datasets are integrated

- More people become involved.

Eventually, the paper needs to be written, figures be done properly, analysis be saved for the scientific record and to document its integrity. Here are a few tools that can help.

- Use an integrated development environment (IDE): RStudio/Posit; VS Code; IDLE…

- Use literate programming tools: Rmarkdown, quarto, JuPyteR.

- Anticipate re-engineering of the data formats and the software.

- Use functions rather than copy-pasting stretches of code.

- Reorganize data upfront rather than repeatedly on the fly.

- Centralize the location of the raw data files, streamline & automate the derivation of intermediate data.

- Reuse existing tools.

- Use version control, such as git.

- Use the R package system.

- Keep a hyperlinked webpage with an index of all analyses.

Data representation

Combining all the data so it is ready for analysis or visualisation often involves a lot of shuffling around of the data, until they are in the right shape and format for an analytical algorithm or a graphics routine.

Errors can occur, lost labels, lost information: be safe, redundancy is good.

Wide vs long table format

A single cell expression data matrix (Hiiragi2013 package) data (only the first 5 rows and columns):

1 E3.25 2 E3.25 3 E3.25 4 E3.25 5 E3.25

1415670_at 4.910459 7.526672 6.956328 6.424048 5.105808

1415671_at 9.768979 9.144228 9.295010 11.059831 9.376749

1415672_at 10.411893 10.918942 9.495738 10.317996 11.143684

1415673_at 5.618108 6.439416 6.730465 4.914527 5.619778

1415674_a_at 7.541891 8.380285 8.480580 7.977363 8.650312[1] 45101 101This is an example for a data table in wide format.

# A tibble: 4,555,201 × 3

probeid `Embryonic Day` value

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 1415670_at 1 E3.25 4.91

2 1415670_at 2 E3.25 7.53

3 1415670_at 3 E3.25 6.96

4 1415670_at 4 E3.25 6.42

5 1415670_at 5 E3.25 5.11

6 1415670_at 6 E3.25 5.86

7 1415670_at 7 E3.25 5.06

8 1415670_at 8 E3.25 4.57

9 1415670_at 9 E3.25 8.12

10 1415670_at 10 E3.25 5.46

# … with 4,555,191 more rowsIn dfl, each row corresponds to exactly one measured value, stored in the column named value. Then there are additional columns that store the associated covariates.

Now suppose we want to store somewhere not only the probe identifiers but also the associated gene symbols.

In dfw, we could stick them as an additional column, and perhaps also throw in the genes’ ENSEMBL identifier for good measure. But now we have a problem: the dataframe now has some columns that represent different samples, and others that refer to information for all samples (the gene symbol and identifier) and we somehow have to know this when interpreting the dataframe. This is what Hadley Wickham calls untidy data.

In contrast, in dfl, we can add these columns, yet still know that each row forms exactly one observation, and all information associated with that observation is in the same row.

Tidy data

In tidy data

each variable forms a column,

each observation forms a row,

each type of observational unit forms a table.

Using tidy data wisely

See also https://www.huber.embl.de/msmb/Chap-Design.html#tidy-data-using-it-wisely

Efficiency (lack of)

Even though there are only 45101 probe-gene symbol relationships, we are storing them 4555201 times in the rows of dfl.

Standardization (lack of)

We may choose to call these columns probeid and geneid, but the next person might call them probe_id and gene_id, or even something completely different. When we find a dataframe that was made by someone else and that contains such-named columns, we may hope, but have no guarantees, that these are valid gene symbols.

Addressing such issues is behind the object-oriented design of the specialized data structures in Bioconductor, such as the class SummarizedExperiment.

Matrices versus dataframes

Representation of the matrix may also simply be more natural and mathematically stringent - e.g., if we want to apply PCA / dimension reduction, or classification.

Summary

There are two types of variation in an experiment or study: those of interest, those that are unwanted.

We usually cannot rid ourselves of all the unwanted variation, but we saw how we can used balanced randomized designs, data transformations.

Reproducible workflows

Open science: make data and code available

Acknowledgments

Quarto sources for this talk: https://github.com/wolfganghuber/Best-Analysis-Practices-Talk

References